|

Universa Investments January 2019 Nietzsche's self-proclaimed fundamental doctrine was a thought experiment: Imagine a demon approached you and declared that you would have to live your life exactly as you have lived it-including your same investment returns, with "every pain and every joy"-over and over again, for eternity. This is Nietzsche's "eternal return of the same" or, in this case, the "eternal return of the same return." At its heart, it's a hypothetical test: "Do you desire this once more and innumerable times more?" Would you kiss or curse the demon? From an investing standpoint, your answer would surely depend on your results, ex post (the actual results). But it's possible to set yourself up ex ante (before you know those results) to say "yes" to that question-and "yes" to your same investing fate forever-regardless of the market's path. This is "amor fati"-the love of one's fate-an existential imperative that is Nietzsche's "formula for greatness in a human being," and is the secret to successful investing.

A ‘Black Swan’ fund that has managed to make money in the great bull market is taking advantage of what it sees as overvaluation and investors’ complacency to reap a far bigger bonanza By Spencer Jakab Sept. 21, 2018 The 10th anniversary of the financial crisis is a natural time to fret about the next bust, but betting against the market is usually a loser’s game. Or is it? Record stock prices, bubbling trade wars, Donald Trump’s legal peril and sputtering emerging markets give some teeth to fears of another market rout. So did a host of mostly forgotten crises—Brexit, the fiscal cliff, the taper tantrum—that turned out to be great buying opportunities. The S&P 500 has returned over 200% since the day Lehman Brothers went bust—more fodder for the investing classic “Triumph of the Optimists” that underlines the benefits of staying in the market through thick and thin. So why is a man who has made a huge wager on another market collapse so happy? It isn’t because he sees an imminent crash, though he doesn’t rule it out. It is because almost no one else is preparing for one. “I spend all my time thinking about looming disaster,” says Mark Spitznagel, chief investment officer of hedge fund Universa Investments, who predicts a major decline in asset prices but can’t say when. He admits that the bull market could keep going for years. “Valuations are high and can get higher.”

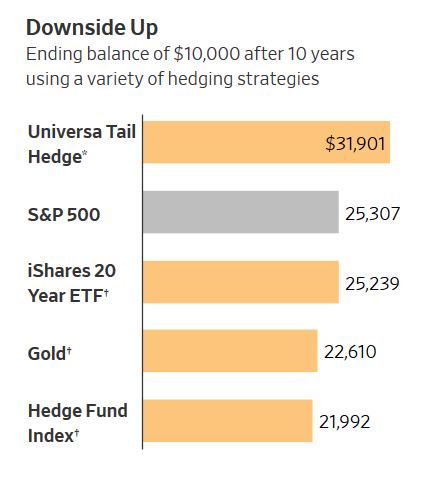

Talk is cheap in investing punditry and predicting a decline without saying when it will happen is cheapest of all. Yet Universa’s stance warrants attention, and not only because it backs its views with billions of dollars and is advised by author Nassim Nicholas Taleb of “Black Swan” fame. Mr. Spitznagel isn’t betting on some unpredictable event causing a crisis but instead a predictable one—an eventual blowback from unprecedented central-bank stimulus. What sets the fund apart and why investors should pay attention is that Mr. Spitznagel’s clients have done well without a crisis. Founded in 2007, Universa was among a handful of funds that made huge gains in 2008. Unlike some crisis-era legends such as John Paulson, David Einhorn and Steve Eisman who have struggled mightily since then, Mr. Spitznagel has enjoyed mini-bonanzas along the way. In August 2015, for example, his fund reportedly made a gain of about $1 billion, or 20%, in a single, turbulent day. A letter sent to investors earlier this year said a strategy consisting of just a 3.3% position in Universa with the rest invested passively in the S&P 500 had a compound annual return of 12.3% in the 10 years through February, far better than the S&P 500 itself. It also was superior to portfolios three-quarters invested in stocks with a one-quarter weighting in more-traditional hedges such as Treasurys, gold or a basket of hedge funds. “This is a very good time for us,” he says. by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

The Telegraph 16 September 2018 The world’s major economies are skating on dangerously thin ice and lack the fiscal, monetary, and emergency tools to fight the next downturn. A roster of top crisis veterans fear an even more intractable slump than the Lehman recession when the current ageing expansion rolls over. The implications for liberal democracy are sobering. “We have no ability to turn the economy around,” said Martin Feldstein, President of the US National Bureau of Economic Research. “When the next recession comes, it is going to be deeper and last longer than in the past. We don’t have any strategy to deal with it,” he told The Daily Telegraph. Professor Feldstein, a former chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisors, described a bleak scenario more akin to the depressions of the 1870s or the 1930s than anything experienced in the post-War era. He warned that a decade of super-low interest rates and monetary stimulus by the US Federal Reserve has pushed Wall Street equities to nose-bleed levels that no longer bear any relation to historic fundamentals. Stock prices will inevitably come plummeting back down to earth. Prof Feldstein said the next bear market - most likely triggered by a spike in 10-year Treasury yields - risks setting off a $10 trillion crash in US household assets. The cascading ‘wealth effects’ will drain the retail economy of $300bn to $400bn a year, causing recessionary forces to metastasize. “Fiscal deficits are heading for $1 trillion dollars and the debt ratio is already twice as high as a decade ago, so there is little room for fiscal expansion,” he said, speaking earlier on the sidelines of the Ambrosetti forum on world affairs at Lake Como. The eurozone faces an even worse fate when the global cycle turns since the European Central Bank has yet to build up safety buffers against a deflationary shock. The half-constructed edifice of monetary union almost guarantees than any response will be too little, too late. “The Europeans don’t have a fiscal back-up. They don’t have anything. At least you have your own central bank and treasury in Britain, so you will be happier,” he said. “Mario Draghi is going to be very happy when he has left the ECB because it is not clear how they are going to get out of this when they still have zero rates. They can’t play the trick of the cheap euro again,” he said. It is striking that bond yields are still negative on maturities of five years or more in Austria, Belgium, Finland, Germany, Ireland, and the Netherlands (though not in France any longer, interestingly). This is evidence of a profound structural malaise. The ECB has already pre-committed to holding its reference rate at minus 0.4pc until late 2019. By then the global economy will be acutely vulnerable since the sugar rush from Donald Trump’s tax cuts and infrastructure spending will have faded. The US is entering uncharted and perilous waters. The jury is out over whether it can - in extremis - follow the example of Japan and push the public debt ratio to stratospheric levels (245pc of GDP). The difference is that the Japanese are the world’s biggest savers and external creditors. The Americans must import capital to finance their twin deficits. Foreign investors own half the stock of US Treasury bonds. They will not fund ballooning deficits indefinitely. Prof Feldstein said Americans will have to cover a bigger share of the burden themselves and this will “crowd out” the US bond markets, with knock-on effects for equities. Olivier Blanchard, ex-chief economist of the International Monetary Fund, said the US has big enough buffers to cope with a “run-off-the-mill” recession but would need to tear up the rule book altogether in a deep downturn. While the Fed’s balance sheet is already “scary” at $4.2 trillion after previous rounds of quantitative easing, it could go a lot higher. “If we need it, we could clearly double it and nothing terrible would happen,” he told a Boston Fed forum on how to fight the next slump. Prof Blanchard, now at the Peterson Institute, said the Fed could buy equities. The Bank of Japan already does this. It is the biggest holder of exchange traded funds on the Tokyo bourse. “This could do the trick and could work even better than buying long bonds,” he said. The Fed could even print ‘helicopter money’ to fund the fiscal deficit directly, an idea floated by academics after the last crisis but deemed too radical for the political system. This variant of ‘people’s money’ injects stimulus directly into the veins of the economy rather than channeling it through asset markets, the post-Lehman trickle down mechanism that has greatly benefited the rich and entrenched wealth inequality. But it is difficult to reverse later when the time comes to drain excess liquidity. While the US could in theory experiment with helicopter money, Congress would be hostile to any such form of monetary adventurism. It would be a last resort. In the eurozone it would be completely impossible under EU treaty law and the restrictive fiscal rules of the Stability Pact. Mr Blanchard said it took at least 850 basis points of rate cuts to fight the post-Lehman recession - directly or synthetically through bond purchases under the Wu-Xia model - and this is clearly not available now. His advice is to delay monetary tightening and run the US economy hot until it is safely out of the deflationary doldrums. A fresh crisis would expose another huge problem. Capitol Hill has tied the hands of the US Treasury and the Fed, raising serious doubts over whether the authorities could legally repeat the crisis measures that rescued the financial system in 2008. The fire-fighting trio of the day - Ben Bernanke, Hank Paulson, and Tim Geithner - wrote a joint article in the New York Times last week lamenting that Congress had stripped the watchdog bodies of “powerful tools”. The tougher rules constrain the Fed’s ability to halt fire-sale liquidation. The Dodd-Frank Act stops it rescuing individual companies in trouble (there must be at least five, and they must be solvent) or lending to non-banks. The Fed cannot issue blanket guarantees of bank debt and money market funds. It can lend only to ‘insured depository institutions’. What saved capitalism in 2008 were lightning-fast moves by the Fed and the US Treasury to shore up the markets for commercial paper and the asset-backed securities markets, and to stop a run on the money market industry. It took $1.5 trillion of emergency loans to halt the vicious cycle. “These powers were critical in stopping the 2008 panic,” they said. It is often forgotten that the Fed also saved the European financial system when the global dollar funding markets seized up in the days after the Lehman and AIG crashes. It became nigh impossible to roll over three-month dollar credits. The ECB and its peers could not create the dollars desperately needed to buttress Europe’s interbank markets. The Fed responded with liquidity swap lines in US dollars to central bank peers, removing all limits over the wild weekend of October 14 2008. Total swaps surged to $580bn. The problem today is that Fed no longer has the authority to do this. It needs the approval of the US Treasury Secretary, and therefore the Trump White House. The worrying question is whether Mr Trump would refuse to “bail out” Europe in a crisis - deeming it their own problem - or might try to use this enormous power as leverage for political or trade policy objectives. In short, it is no longer clear that there is a lender-of-last resort standing full square behind the dollarized global financial system and able to act instantly in a crisis. Gordon Brown warned last week that lack of global solidarity threatens to leave a poisonous situation when the next storm hits. Almost all the policy survivors of the last crisis agree with him. Bloomberg

22 September, 2018 Ten years after the financial crisis, with the bull market now the longest on record, "black swan" fund Universa Investments chief investment officer, Mark Spitznagel, spoke on Bloomberg TV and said that "we are going to continue to see deeper and deeper [crashes], simply by virtue of the fact that the degree of interventionism is larger and larger." In other words, trading for "the end of the world"... but not expecting it to come tomorrow. In fact, his advice to traders is simple: "you mustn’t fight the Fed. What you must try to do is sort of jiu-jitsu the Fed. You need to sort of use the Fed’s force against it." Easier said than done? For most, yes: founded in 2007, Universa quickly rose to fame the very next year when it made huge profits in the crash of 2008. On the other hand, as the WSJ wryly notes, "being skeptical and making money on that view are two different things." Fellow financial crisis standout John Hussman, who predicted both the 2000 and 2008 bear markets, is convinced an even worse one is coming, yet his own fund has performed dismally since 2009, eroding its crisis gains and then some. This is where Universa stood out. Unlike John Paulson, David Einhorn and Steve Eisman who made stellar returns during the crisis but have failed to repeat their success since, Spitznagel has enjoyed several mini-bonanzas along the way. During the ETFlash Crash of August 2015, his fund reportedly made a gain of about $1 billion, or 20%, in a single, unforgettable day. But was that performance repeatable, and could it beat the market in the long run... and certainly before the inevitable crash? To be sure, as the WSJ's Spencer Jakab writes, "talk is cheap in investing punditry and predicting a decline without saying when it will happen is cheapest of all." Yet Universa’s stance warrants attention, and not only because it backs its views with billions of dollars: Spitznagel isn’t betting on some unpredictable event causing a crisis but instead a predictable one—an eventual blowback from unprecedented central-bank stimulus. And while so far the "final crash" has yet to come, what has made the "fat tail" fund unique - recall that Universa is advised by author Nassim Nicholas Taleb of "Black Swan" fame, and best known for his prediction that six sigma "fat tail", or black swan, events happen much more frequently than they should statistically - is that it has not only not lost money, but has actually outperformed the S&P in the past decade: According to a letter sent to investors earlier this year and seen by the WSJ, a strategy consisting of just a 3.3% position in Universa with the rest invested passively in the S&P 500, had tripled the money, generating a compound annual return of 12.3% in the 10 years through February, better than investing in just the S&P 500 itself. It also was superior to portfolios three-quarters invested in stocks with a one-quarter weighting in more-traditional hedges such as Treasurys, gold or a basket of hedge funds. This is how the fund described its performance: In our ten-year life-to-date, a 3.33% portfolio allocation of capital to Universa’s tail hedge has added 2.6% to the CAGR of an SPX portfolio (the SPX total CAGR over that period was 9.7%). To put this in perspective, this is the mathematical equivalent of that same 3.33% allocated to a ten-year annuity yielding about 76% per year. In contrast, each of the other risk mitigation strategies actually subtracted value over the same period, regardless of their allocation sizes. The 3.33% portfolio allocation size to Universa was chosen because it is (and has always been) the approximate effective allocation size recommended in practice at Universa (relative to a client’s total equity exposure). The 25% portfolio allocation size to the other risk mitigation strategies was chosen to be meaningful and realistic for an average investor (relative to their total equity exposure). That turned out to be insufficient for any of those strategies to provide a level of downside protection anywhere close to the level Universa provided. There is no magic to this outperformance: Spitznagel has traditionally buys put options, especially when they are cheap, like now for example, when despite bubbling trade wars, Donald Trump’s legal peril and sputtering emerging markets, have failed to dent the market's ascent to new all time highs. By pointedly ignoring headlines and embracing long stretches when his fund loses small sums for months on end, he draws on similar patience and conviction. As shown in the chart above, Spitznagel's small crash bets have paid off repeatedly, offsetting the "theta bleed" associated with a portfolio such as his. Which may also explain why Spitznagel is so happy: it isn’t because he sees an imminent crash, though he doesn’t rule it out. It is because almost no one else is preparing for one. “I spend all my time thinking about looming disaster,” says Mark Spitznagel, chief investment officer of hedge fund Universa Investments, who predicts a major decline in asset prices but can’t say when. He admits that the bull market could keep going for years. “Valuations are high and can get higher.” Another quirk: in 2017, when volatility dropped to all time lows, buying crash insurance was seen by many as throwing away money. But Spitznagel said he was “like a kid in a candy store” because volatility, and hence options prices, were so subdued. At least they were until February of this year, when the VIX underwent a record explosion, soaring from the single digits to an all time high handing Universa's clients another outsized return with a true market hedge. Just sitting out the market in the long run is costly, which is why optimists triumph. Universa’s typical client suspects that the end may be nigh but wants to stay fully invested anyway. The occasional windfall, such as the one in 2015, is icing on the cake. Ultimately, the math behind Spitznagel’s investing philosophy is a simple bet on human nature: investors are "more confident after a long stretch of smooth sailing and hefty gains for markets, that is when the odds of something going horribly wrong are highest." And with the S&P at all time highs, Spitznagel has to be delighted: after all, both investor confidence, and the odds of that "horribly wrong" moment are just as high. "This is a very good time for us," he said. Now all he needs is a crash. One might have expected that the near-death experience of most investors in 2008 would generate valuable lessons for the future. We all know about the “depression mentality” of our parents and grandparents who lived through the Great Depression. Memories of tough times colored their behavior for more than a generation, leading to limited risk taking and a sustainable base for healthy growth. Yet one year after the 2008 collapse, investors have returned to shockingly speculative behavior. One state investment board recently adopted a plan to leverage its portfolio – specifically its government and high-grade bond holdings – in an amount that could grow to 20% of its assets over the next three years. No one who was paying attention in 2008 would possibly think this is a good idea.

Below, we highlight the lessons that we believe could and should have been learned from the turmoil of 2008. Some of them are unique to the 2008 melt-down; others, which could have been drawn from general market observation over the past several decades, were certainly reinforced last year. Shockingly, virtually all of these lessons were either never learned or else were immediately forgotten by most market participants. Twenty Investment Lessons of 2008

Below, we itemize some of the quite different lessons investors seem to have learned as of late 2009 – false lessons, we believe. To not only learn but also effectively implement investment lessons requires a disciplined, often contrary, and long-term-oriented investment approach. It requires a resolute focus on risk aversion rather than maximizing immediate returns, as well as an understanding of history, a sense of financial market cycles, and, at times, extraordinary patience. False Lessons

“The way to build long-term returns is through preservation of capital and home runs.”

“Everyone sort of lives with their rulers in the past and doesn’t look at coming changes.” “Earnings don't move the overall market; it's the Federal Reserve Board... focus on the central banks, and focus on the movement of liquidity... most people in the market are looking for earnings and conventional measures. It's liquidity that moves markets.” Stanley Druckenmiller Fed critic who predicted previous 2 market crashes says timing can't be predicted, but causation can be determined Value Walk Magazine by Mark Melin July 10, 2018 Is Mark Spitznagel the most misunderstood hedge fund manager on “Wall Street?” The man ultimately responsible for decisions at Universa Investments L.P., a tail risk mitigation strategy with nearly $6 billion under management, has been described as “betting on doomsday.” But in an exclusive ValueWalk interview, he opened up about a strategy that actually helps diversified portfolios in both up and down markets, slapping a strategy stereotype in the face. This Midwestern-born, Chicago-raised risk manager – a look that has been characterized as “boring” in a lecture given by author Malcolm Gladwell — is the antithesis of a “boring” traditional 60% / 40% portfolio allocation between stocks and bonds.* While Wall Street’s long-only mindset might consider him as some sort of an anachronism, setting himself apart by considering a diversification method using bonds and clearly claiming the emperor has no clothes. That’s not boring. Challenging the prevailing thought process on a little island of thought, opening up new avenues for risk management, is exhilarating to Spitznagel. But once the nuanced dichotomy of what some consider revolutionary is understood – looking at the stock market opportunity lost by investing 40% of a portfolio into low returning bonds – then the importance of end-point investing becomes apparent to volatility conscious investors near the end of an economic cycle. The dichotomies in today’s absurd world are clear to those who actually seek real answers. How can Spitznagel be best known for predicting the 2001 and 2008 market crashes but such brilliant analysis didn’t play any role in why his hedge fund delivered strong returns during such weak markets? Forecasting markets is fruitless, says the man who predicted the previous two. The dichotomy exists for the same reason the fund manager known deep in alternative investment circles for using a “long volatility” strategy also revealed that short volatility is no stranger to the portfolio. Market soothsaying has no impact on Universa’s day-to-day investment strategy, Spitznagel said with an important caveat. The 47-year-old fund manager pointed to his next prediction of a forthcoming markets crash, reiterating a theme. The man who predicted the previous two says he can’t predict exactly when the market will get it, but that market price adjustment will happen, leading to a question. Can Spitznagel see core market causation for three market crashes in a row, something yet to be accomplished by any major hedge fund manager? In this three-part series, we first take a look at Spitznagel’s economic theory to understand why he thinks the market will crash, then we explain how Universa’s strategy works and finally explore how his investment mind was shaped, leading to an uncommon approach that comes from a little-known sect deep inside what is generally considered “Wall Street.” Spitznagel doesn’t have the look of a radical. His placid if almost “boring” Midwestern face belies a man with a strong spine and deep convictions to an investment philosophy that largely shuns the weak consensus. His current market view, that another market price adjustment is inevitable, coalesces with other voices that think excessive central bank interventionism will collapse under its own weight. The “systematic mispricing of risk,” as author William Cohan recently called it in Vanity Fair, is documentable on several levels: sovereign bonds trade at negative real interest rates while stocks and junk bond values approach historic high valuations being among several concerns. While the opinion that the market is overvalued is not as novel as it was in 2008 or leading up to the 2001 “Tech Wreck,” understanding Spitznagel requires understanding not one but two distinct philosophies. There is a market outlook that, in part, has Chinese roots. And then there is a very different investment philosophy that is guided by separate principles that have derivatives at their root. And then there has been his time spent in the global derivatives industry, where he learned from a very particular “Chicago school” of thinking that is very different from “Wall Street.” The Austrian School of Economics has different definitions Former US Fed Chair Alan Greenspan is credited with having his economic thinking rooted in an Austrian School of “free market” thinking to which Spitznagel outwardly subscribes. This concept was taken to an extreme when Greenspan declared to then crusading CFTC Chair Brooksley Born that there wasn’t “a need for a law against fraud” because the market would take care of white-collar criminality. This thinking didn’t wear well nearly two decades later as the largest and most influential banks have racked up historic levels of fines for illegal mischief and have not been punished by markets, delivering among their biggest profits in their history. Spitznagel, like Greenspan, has faith in free markets, but he is also rooted in dogged realism. “Governments can play a role in enforcing contracts, and keeping markets honest, and enforcing torts, etc.,” he pointed out, while also muttering that “markets do that better, of course.” His pressing concern isn’t bankers engaging in repeated acts of market manipulation for profit but central bankers tipping those same scales of free markets to keep interest rates low. In his mind, the Alan Greenspan era, which stated in 1987, was also a time of unprecedented central bank intervention that has created a pattern of markets overheating and resetting ad nauseum. He said its “a pretty dependable rule of thumb that governments have a way of screwing up virtually everything that they touch” when entering free markets. “They try to make some aspect of the economy or markets or the world better and they end up getting the opposite. It’s almost a cliché.” What is odd, however, is that seldom do the “official” market manipulators get challenged in a respectful format. While many economists disagree with Greenspan – some sharply – there is mostly agreement in the derivatives markets in which Spitznagel trades that markets are a tool for price discovery. Markets are designed to measure economic supply and demand. When demand exceeds supply the price goes up and vice versa. These are core performance drivers that are first understood as a frame to evaluate more complex issues. So what happens when a central bank puts its hand on the market scale too harshly? “The next market crash will be greater than any in human history,” Spitznagel told ValueWalk. “The monetary intervention we’ve seen since 2008 is unprecedented. Something destructive always happens when a government sets prices.” Spitznagel’s warnings come at an odd time, as what is rapidly becoming the failed state of Venezuela learns the lessons of market repression. Kids have been reported in the streets throwing bolivars, the nation’s currency, into the air as rampant inflation makes them worth nothing more than the paper they are printed on. Spitznagel doesn’t want this to be the future, which is one reason he raises the issues, particularly in regards to market manipulation. While extreme, such central economic planning has a history of ending badly in places such as the former USSR and other communist regions. While the US has been considered to be a “free market system,” he sees a strategy drift with an invisible hand coming into play. “We have this strategy creep by central banks since the 1980s,” he said, pointing to a general lack of concern regarding the impact of central bank interference on free markets. “We get desensitized. It is hard to question something that is working for you.” But that is part of the problem. Central bank monetary intervention can provide a tranquil look to the markets when interest rates are low. But the longer the free market repression, the worse the consequences. Spitznagel’s worst fear is that monetary repression will lead to inflation, which many business models can’t handle, a point he made: It would be painful for a lot of people in the short run and that is a really bad thing. At the same time, it would allow capital to be deployed in a much more rational and effective way. Right now we have companies alive today that should not be alive today. And that capital should go to other, more productive places. The progress of civilization slows down when capital is allocated as irrationally as it is today when interest rates are artificially set. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed