|

A Conversation with Mark Spitznagel American Consequences by P.J. O’Rourke June 2018 One of my favorite investors is Mark Spitznagel. Of course, I admire his success. He is the “Ursa Major” among bears, having correctly (and very profitably) called the stock market crashes of 2000 and 2008. Since then he has “fenced the bull” with his multibillion-dollar Universa Investments hedge fund that not only actually hedges (something many hedge funds, busy making huge derivative bets, forget to do) but is also structured to profit in rising markets. Mark is an intellectual investor. In his book, The Dao of Capital, he combines the rigorous logic of libertarian Austrian economics with the Chinese philosophical tradition of harmonious flow of natural forces. (Hint: Central banks aren’t a natural force.) Forbes magazine called it “one of the most important books of the year, or any year for that matter.” But what I like about Mark is that he’s fun to talk to. You can tell by choosing almost any quote at random from Dao: The real black swan problem of stock market busts is not about a remote event that is considered unforeseeable; rather it is about a foreseeable event that is considered remote. The vast majority of market participants fail to expect what should be, in reality, perfectly expected events. Mark is also an unrepentant Heartlander, born and raised (and raising his family) in Michigan, a graduate of Kalamazoo College who can still recite his college yell Breck-ki-ki-kex! Ko-ax! Ko-ax! Whoa-up! Whoa-up! Paraballou! Paraballou! Kalamazoo! Kazoo! Kazoo So, what did he do when he got rich? He started a goat farm.

Idyll Farms, in Northport, Michigan, produces artisanal chèvre from pastured goats (not grain-fed, cooped-up nannies). The cheese has won Best in Class at the World Championship Cheese Contest and multiple awards, including Best All-Milk Cheese, from the American Cheese Society. And if praise like that from the American Cheese Society doesn’t make your heart skip a beat, you should get out of the Heartland and stay out. Mark seemed to be the right person to ask about the main thing that puzzles me about the Heartland – its vast array of undervalued assets. He and I discussed how the Heartland is full of famously sensible, friendly, and hard-working people. It contains a large portion of the most productive agricultural land in the world. The housing stock is extensive and cheap. Industrial sites and commercial locations are ready and waiting. Natural disasters – minus the occasional tornado – are rare. The climate is temperate. The location is central to every form of transportation. We talked about how the Heartland has water to shame the West, educational attainment that’s the envy of the South, and a freedom from congestion about which the East can only dream. “Why isn’t the Heartland booming?” I said. Mark described it as “a chicken and egg problem.” He said that the Heartland would boom if millennials, and “knowledge workers” in general, wanted to live there, but those people would want to live in the Heartland only if the Heartland boomed. Mark told me about moving out of Los Angeles and back to Michigan because of the values (moral and material) that the Heartland offers… and because of the anti-business attitude that California maintains. But it was his family that he moved. He moved his company to Miami and now commutes north-south. (Mark inexplicably claims to more than make up for his jet-setting carbon footprint with his hippie, carbon-sequestering goat pastures.) “Why not move your business to Michigan?” I asked. “There’s just a general expectation of where a hedge fund like mine should reside. And it’s because of the people I need to hire,” he said. “It’s about where these hip ‘quanty’ geniuses want to live.” I said, “Maybe if Amazon put its second headquarters in Kalamazoo…” “But it has to be cool to work for Amazon.” Mark noted, however, that Kalamazoo does have a craft beer – Bell’s. He also noted, “Be careful what you wish for.” And true, a Heartland overrun with Seattle sensibilities would take the heart out of the place. But in Mark’s view, Heartland difficulties run deeper than the location whims of talented people. The problem is that Heartland assets are hard assets – a wealth of land, infrastructure, and workforce. “Our central bank monetary-led boom has made debt replace wealth for a long time. That’s not sustainable, of course. (We are ‘mining’ our soil for short-term gain.) We’ll see a return to the significance of productive stuff again I think, and that even includes farming – maybe especially farming. And the Midwest has a pretty good track record with productive stuff. Hard assets will matter again. But of course, I sound ridiculous even saying such things. Like a grumpy old grandpa.” Artificially low interest rates have sent people off to chase yield in softer kinds of assets – causing asset bubbles. Yield-chasing can’t last. It’s not good business. And the places where the yield-chasing is being done aren’t the places where good businesses will be built. The Heartland states, Mark said, have to “be like Texas – better yet, Switzerland – business friendly.” And he said they were getting there. “Michigan is a right-to-work state now.” (Meaning that employees can’t be forced to join unions against their will.) This once would have been unimaginable in the state that was Jimmy Hoffa’s home (and probable burial site after he disappeared on the way to lunch with two Mafia members). Mark talked about how federalism is working “the way the founders wanted it to work. People are leaving states that aren’t business-friendly. They’re voting with their feet.” “Hard assets will return,” Mark said. “The Heartland will be back. It will matter again.” by Brian Stoffel

April 3, 2018 The Motley Fool Stoffel: I read recently that you gave an interview -- I think it was on Bloomberg -- where you talk about where your own skin is in the game. One thing you wrote is that it is not rational to be long stocks without having some sort of hedge against stocks. That's because their valuations are so high, because there are tail risks...? Taleb: No -- even if the valuations were low. If the market delivers a crazy valuation, it can deliver a crazy valuation in any direction. Stoffel: So, for your normal person who works as a plumber or an electrician, what is a good hedge against stocks? Just cash? Taleb: Well, the point is as follows: if your assets are $100 and you allocate $50 to stocks, then you are ergodic -- assuming those $50 are allocated to stocks, you don't want to decrease them at any point in time. Let me explain the foundation of the problem: All of these analysts who look at you and the stock market assume that if you invest in the stock market, you'll replicate the performance of the stock market. The problem is, if you ever have an "uncle point" -- where you have to liquidate -- then your return will not be the stock market's. It will be the returns to your "uncle point" -- which is negative. In other words: The market can have a positive expected return, and you have a negative expected return. It's very similar to Russian roulette. Russian roulette is a very simple example. If you play Russian roulette with a positive expected return of 80% -- or, whatever it is, five out of six? Stoffel: I haven't played, so I'm not sure [laughter]. Taleb: [laughter] You can't cheat to be dead. So it's the same thing with casinos. If you gamble in a casino at a roulette table, even if you have a positive expectation, you're guaranteed -- eventually, at some point -- to go bankrupt ... even though you had a positive expectation. Stoffel: And that's the difference between ensemble [average] and time [average], correct? Taleb: Exactly. Because probability over time depends on what happened right before. Whereas probability of the ensemble doesn't have to worry about what happened before it. So you have that discrepancy...when you invest. So as an investor you need to think about it in these terms: no investor knows what's going to happen to him or her in the future. You don't know -- I mean, the market may deliver whatever people claim it will deliver. But if you have a drop in the market that may force you to liquidate -- particularly a drop in the market that may correlate with your loss of business elsewhere -- then, automatically, your returns will be the returns from today until that drop in the market. It de-correlates from the market. And this is not well understood by finance people... unless you trade. I know a lot of people, for example, when I was short bonds. When I'm short bonds, people think that, hey, typically I will lose money if the market rallies. And the opposite actually happens. I tend to make money when the market rallies although I'm short. Because -- typically -- you pick your points -- maybe you're only short for 30% of the year, not the whole year -- so you're dynamically hedged. And you pick your points, and you go in and out. So I noticed over time -- for example -- my best returns from markets are the opposite of what the market has done. So negative correlation. That's simply because I'm long the markets, typically. And I like to buy after dips -- just buy after dips... even in a bear market. And of course, get out after the market recovers. Even in bear markets, you can make money. This is well understood by traders. Traders say the direction of the market doesn't matter much. It's your techniques that matter. But for investors, the same applies, unless this is an amount of money that you will never liquidate, and you transmit across generations. What I've been doing is saying: If you have an investment -- as an institutional investor, forget the individual investor -- and you don't have a tail-hedge protection, then your returns are virtually going to be zero -- over the long run. Stoffel: Because it's the same as playing Russian roulette... Taleb: Exactly. If you have tail-hedge protection, then your return will be higher than the market. Because ... you can get more aggressive during the times when people sell. This is not well understood. My strategies have been to overload with tail options ... and not because you get a good payoff if the market collapses. It's because it allows you to buy when nobody has dry powder. Stoffel: It's basically the same for an individual investor as having a huge chunk of cash sitting on the sidelines that they can use to buy stocks low. Is that correct? Taleb: Yes, but the problem is for the individual investor if you miss the rally. You see, I have a larger exposure to the rally -- and my exposure increases via options on the way down. I don't recommend individual investors use options. The risk of having a lot of cash is that if the market rallies -- for the individual investor, it doesn't work well -- you have all this cash, you missed on a big move. Stoffel: And you never know when your time is going to come. So you're losing to inflation as well. Taleb: Exactly. So the idea -- the wisest and most appropriate approach -- is to let the institutional investors have the tail hedges themselves. Or to do what I call the barbell: to have a smaller amount allocated to the most volatile things, rather than a larger amount allocated to medium-volatile things. There are techniques around it. It took me 28 years to figure out the flaws in the models proposed by so-called academics -- people without skin in the game. Stoffel: Like the Scholes model? Taleb: No -- the Scholes model is for fat tails. They're all connected, but there's one central thing: Even if you're not using the Gaussian distribution, you're still long. And it's analyzing things as one step rather than analyzing life as a series of steps. Ironically, that's my first book: Dynamic Hedging. That's my first activity -- dynamic hedging. When you look at the activity, you're trying to figure out, "What's the smartest approach I can have given the opacity of things?" Excerpted:

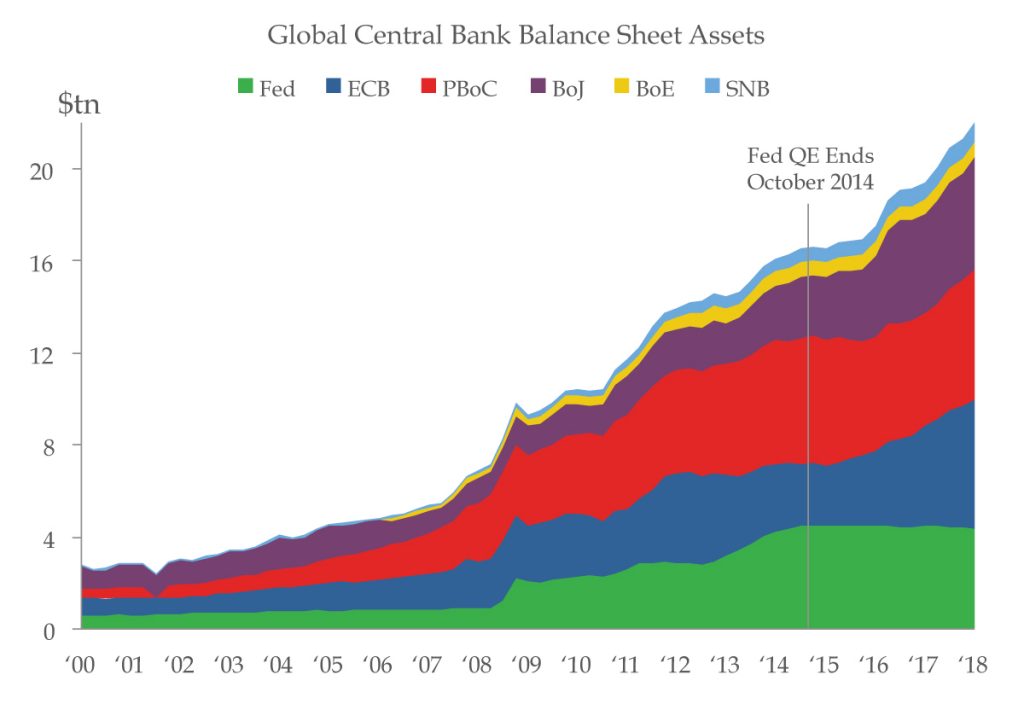

...government debt, which has doubled over the last decade, is set to increase to levels only reached during World War II over the next decade, so we will have sacrificed our future during a relatively peaceful economic period with no post-war reduction simply because politicians can’t say no. This does not exactly measure up to spending to defeat fascism and defend the world’s freedom. Finally, let me address a distortion that is one of the greatest threats to a properly functioning capitalist system. For years now a mix of central – sorry – for years now a mix of financial repression and central bank intervention has made long-term interest rates largely determined by government fiat. Bond-buying by central bankers, commonly referred to as QE, has become so engrained in current thinking that it is now in the Fed’s conventional toolkit, a tool once reserved for a depression or financial crisis is now to be used at the first inkling of the next recession. For those of us old enough to have seen the dangers of price controls, they led to shortages, wasted resources, and disincentives to invest in what consumers want. They inevitably led to an allocation of resources by political actors in another great affront to capitalism. So, it is most surprising that 40 years after wage and price controls were sadly rejected by every economic textbook and policymakers, today we have settled to allowing the most important price of all, long-term interest rates, to be regularly distorted by public intervention. The excuse of this radical monetary policy has been the obsession with a fixed 2.0% inflation targeting rule. The decimal point shows the absurdity of the exercise. Anything below 2.0% was a failure and risked deflation, the boogeyman of the 1930s, to be avoided at all costs. This has meant that years after the Great Recession ended the Fed has not only kept interest rates below inflation but have accumulated an unprecedented $4.5 trillion on their balance sheet by doing QE. Global central banks, in part to keep their currencies from appreciating of these overabundant dollars, have followed with $10 trillion of their own. Now, the irony of this is, over the last 700 years, inflation has averaged barely over 1% and interest rates have averaged just under 6%. So, we are seeing an unprecedented, ultra-monetary, radical monetary expansion during a time of average, average inflation over the last number of centuries. Moreover, the three most pernicious deflationary periods of the past century did not start because inflation was too close to zero. They were preceded by asset bubbles. If I were trying to create a deflationary bust, I would do exact exactly what the world’s central bankers have been doing the last six years. I shudder to think that the malinvestment that occurred over this period. Corporate debt has soared, but most of it has been used for financial engineering. Bankruptcies have been minimal in the most disruptive economy since the Industrial Revolution. Who knows how many corporate zombies are out there because free money is keeping them alive? Individuals have plowed ever-increasing amounts of money into assets at ever-increasing prices, and it is not only the private sector that is getting the wrong message, but Congress as well. I have no doubt we would have not gotten such a big increase in fiscal deficits if policy had been normalized already. Of all the interventions by the not-so-invisible hand, not allowing the market to set the hurdle rate for investment is the one I see with the highest costs. Competition is a better tool than price control for protecting consumers. That applies to Amazon and the bond market. The government should get out of the business of manipulating long-term interest rates and canceling market signals. by Adrienne Westenfeld

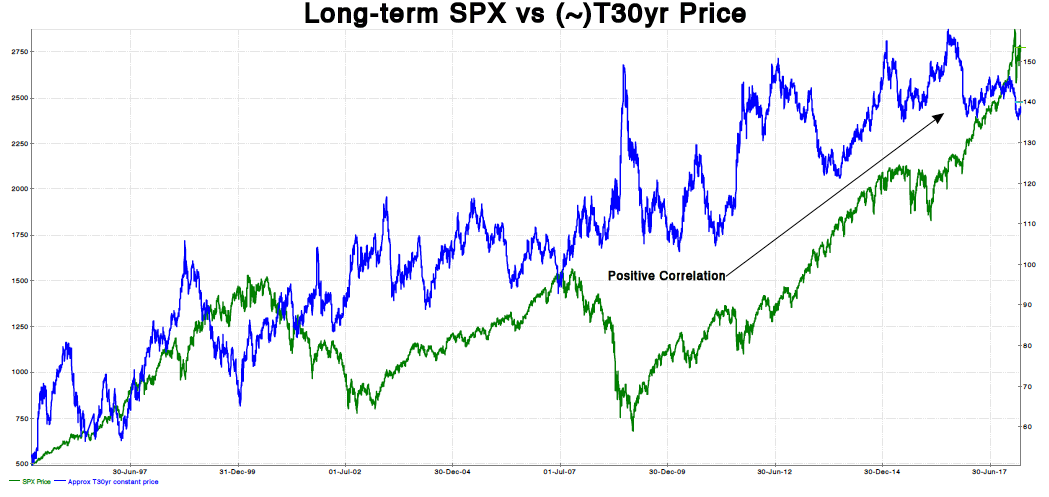

Esquire 20 April, 2018 People ask me my forecast for the economy when they should be asking me what I have in my portfolio. Don’t make pronouncements on what could happen in the future if you’re immune from the consequences. In French, they use the same word for wallet and portfolio. I have never, ever borrowed a penny. So I have zero credit record. No loans, no mortgage, nothing. Ever. When I had no money, I rented. I have an allergy to borrowing and a scorn for people who are in debt, and I don’t hide it. I follow the Romans’ attitude that debtors are not free people. I carry euros, dollars, and British pounds. What I do with my money is personal. People who say they give it to charity, that’s a no-no in my book. Nobody should ever talk about a charitable act in public. Better to miss a zillion opportunities than blow up once. I learned this at my first job, from the veteran traders at a New York bank that no longer exists. Most people don’t understand how to handle uncertainty. They shy away from small risks, and without realizing it, they embrace the big, big risk. Businessmen who are consistently successful have the exact opposite attitude: Make all the mistakes you want, just make sure you’re going to be there tomorrow. Don’t invest any energy in bargaining except when the zeros become large. Lose the small games and save your efforts for the big ones. There’s nothing wrong with being wrong, so long as you pay the price. A used-car salesman speaks well, they’re convincing, but ultimately, they are benefiting even if someone else is harmed by their advice. A bullshitter is not someone who’s wrong, it’s someone who’s insulated from their mistakes. There is less “skin in the game” today than there was fifty years ago, or even twenty years ago. More people determine the fates of others without having to pay the consequences. Skin in the game means you own your own risk. It means people who make decisions in any walk of life should never be insulated from the consequences of those decisions, period. If you’re a helicopter repairman, you should be a helicopter rider. If you decide to invade Iraq, the people who vote for it should have children in the military. And if you’re making economic decisions, you should bear the cost if you’re wrong. Ninety-eight percent of Americans—plumbers, dentists, bus drivers—have skin in the game. We have to worry about the 2 percent—the intellectuals and politicians making the big decisions who don’t have skin in the game and are messing the whole thing up for everybody else. Thirty years ago, the French National Assembly was composed of shop owners, farmers, doctors, veterinarians, and small-town lawyers—people involved in daily activities. Today, it’s entirely composed of professional politicians—people who are just divorced from real life. America is a little better, but we’re heading that way. Money can’t buy happiness, but the absence of money can cause unhappiness. Money buys freedom: intellectual freedom, freedom to choose who you vote for, to choose what you want to do professionally. But having what I call “fuck you” money requires a huge amount of discipline. The minute you go a penny over, then you lose your freedom again. If money is the cause of your worry, then you have to restructure your life. The best money I’ve ever spent has been spent on books. The stupidest thing I’ve ever spent money on? Books. Also, I cannot understand why anyone would spend any amount to enhance their social status. If nobody’s paying my salary, I don’t have to define myself. I find it arrogant to call yourself a philosopher or an intellectual, so I call myself a flaneur and I refuse all honors. As Cato once said, it’s better to be asked why there is no statue in your name than why there is one. The Convexity Maven "How Will I Know..." by Harley S. Bassman March 19, 2018 Excerpt: Risk Parity’s tremendous success is revealed via the –pummelo line- of the SPX price in the chart above and the –santol line- of the price of a constant 30-year treasury bond. Risk Parity portfolios have been ‘levered long’ assets that have both increased in value. (We used to call this a Texas-hedge.) Here is the bottom line: If this correlation turns negative so that both stock and bond prices decline, Risk Parity portfolios will be modified to reflect these new correlations and volatilities. In simple terms, they will sell. Risk Parity portfolios will not remain levered long if both assets are declining.

by Mark Spitznagel

Pensions & Investments March 9, 2018 A common refrain among pundits today, in response to the more volatile markets recently and the potential for even more to come, is to point to the historical average annual return of stocks — for example, the S&P 500 total return over the past decade of 10.4%. That's been better than pretty much anything else. While this is true — and even if you were unfazed by the unsettling prospect of likely far less central bank accommodation ahead — this buy-and-hold strategy ignores an important, although perhaps subtle, part of the story. When it comes to investing in hopes of capturing the market's long-run average returns, you can't always get what you want. The average market return is an elusive thing. It doesn't even really exist, in practice. A decade ago, if you had possessed a crystal ball informing you about that nice 10.4% average annual return to come, you would have likely mentally compounded a nest egg of, for instance, $1,000 invested in the S&P 500 into an expectation of roughly $2,690 in capital 10 years later, as of the end of last year. This is just from the simple math of compounding: (1+.104)^10 =2.690 This would have been a good textbook mathematical expectation of your geometric growth in capital. But your expectation would have been quite wrong. Turns out, when compounding market returns over time, the average that you get isn't always what you want. It is highly "non-ergodic"— the "time average" compound rate just isn't computable based on the expectation of that average (the "ensemble" average). Sadly, your perfectly forecast average wouldn't have translated into value at the end, and your expectation was entirely inaccessible. Why? The very thing that seems to be on everyone's minds today: Volatility. Volatility is destructive. It eats away at the rate at which capital compounds in a portfolio over time. We know how this works intuitively: Lose 50% one year, make 100% the next, and you've experienced an impressive average return of 25%, yet you just barely made it back to even. By the same compounding consequences, that $1,000 back in 2008 actually would have become only $2,261 today, an average annual return of about 8.5% — far less than your assumed 10.4%. There was a "volatility tax," as I call it, amounting to about $429 (or about 16%) imposed on your capital. (That's an even higher tax than they pay in New York City!) The S&P 500's volatility wrought havoc on the compounding of that $1,000. In quantitative finance parlance, we can see how this works by considering that the compound (or geometric) average return is mathematically just the average of the logarithms of the arithmetic price changes. Because the logarithm is a concave function (it curves down), it increasingly penalizes negative arithmetic returns the more negative they are, and thus the more negative they are, the more they lower the compound average relative to the arithmetic average — and raise the volatility tax. (While this logarithmic effect is quite independent of the particular return distribution of those arithmetic returns, it so happens that the S&P 500's 19.3% volatility over the past decade imposed the very same volatility tax that we would have calculated assuming the flawed "lognormal" assumption of arithmetic returns, namely .104 - .1932/2 = .085). What can we do about this non-ergodicity problem, which causes us to so miss our expectations? We need to find a way to narrow the gap between our ensemble and time averages. (In the gambling literature there is a useful solution called the "Kelly criterion"— and in fact much of this, and my investing, is but an interpretation of that). The good news is the entire hedge fund industry basically exists to help with this — to help save on volatility taxes paid by portfolios. The bad news is they haven't done that, not at all. Any amount of that $1,000 invested in, say, the HFRI Fund Weighted Composite index in 2008 would have added even more to your cost over the next decade ($100, or 10%, allocated to the HFRI hedge fund index, rebalanced annually, would have cost you $96). Ditto bonds ($400 allocated to the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond index, rebalanced annually — as in the traditional 60/40 stocks-bonds allocation — would have cost you $247). Even today's celebrated "long volatility" strategies would have barely added value ($100 allocated to the Cboe Eurekahedge Long Volatility index, rebalanced annually, would have added just $38). Most "risk mitigation" strategies simply haven't deserved the moniker. "Diversification"— modern portfolio theory's answer to this vexing non-ergodicity, volatility tax problem — hasn't really worked, at least not without ironically utilizing leverage. (This begs the question: What was diversification even good for?) So much for modern portfolio theory. The moral of the story: Let's not rely on the market's historical average return to buy-and-hold ourselves to presumed safety. Buy-and-hold is not an effective risk mitigation strategy (and neither is diversification, for that matter). It's more like a hope and a prayer for low volatility. Yes, the market's historical average return has been pretty good up until now (thanks, in large part, to the Federal Reserve keeping interest rates low for an extended period). But, even if that average persists, you can't always get it. In fact, thanks to market volatility, you likely never will. --- Mark Spitznagel is founder and chief investment officer of Universa Investments, Miami. This content represents the views of the author. It was submitted and edited under P&I guidelines, but is not a product of P&I's editorial team. Transcript: Friends. Let's discuss the problem forecasting one same time explaining the XIV ex trade the VIX. A bunch of people stress of the contract saying the VIX is overpriced mispriced as volatility is over forecast of what's going to happen. The variation in the market the contract. Is poorly designed let's make money off of that. And they were right but they were destroyed and lost all of this money. Why. Because they didn't realize that forecasting has nothing to do with PNL nothing to do with where you live. What matters is if they are watching. So these people are right. You invest if you invest invested say twenty five dollars you would have made some money. I think a high of 46 dollars overtime. And in one one a couple of days they lost everything. It's now at Faisal's and probably these senators will be lower. So what what did they do that was wrong. What they did is not understand that being right on a random variable X doesn't mean making money out of it your pay or function of x needs to be aligned with what you're forecasting. And in fact the function of x is never X and X can be very complicated and realize most people think you've got to focus on X or academics or other idiots. Of X is what you what you focus on when you make the decision. It's much easier to understand your function of running a variable than a version of itself. That's what I said. It's what antifragile. Very few people are getting it. [00:01:57] Academics cannot get the idea that you don't have to be right about the world. You has to make decisions that are convex other with the sort of that makes sense and in fact you don't have to be. And this also explains why paranoia is entirely justified. If you're F of X as concave so you overpricing underpricing probabilities is not what matters. What matters is your payoff. So let's see what happened here. Let's stick your pal function. Remember you have a function of this appoint anyo. You know pretty much everything in life is some nonlinear function that can be expressed through and putting on the model as you add these functions. And of course you can do a more sophisticated way. That's pretty much what it is. This is a wait for us to understand first. Not nearly so. You plot one X square. You see what happens here and I build a function of a vector x. Cap X is a vector is the mean 1 minus X square. So what does it do here. You say with a vector like x 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 is 1. And as for next year it would be zero. OK so that's a function. So let's do a thought experiment another thought experiment x x itself C is 1 1 0 1 1 1. The mean of X is point 7 1 and of course are going to make money because the same is going to be lower than 1 1. Is your price at which you're forecasting otherwise. Or are you starting off with the lower than 1 or higher level and you have a concave payoff. [00:03:45] So you think the average is going to be lower than one your average is lower than one you may point to eight because it's submitted in a certain way. That sort of works. But now if I take the same average was X to 0 0 0 0 0 and then 5. In other words it all came on a variation came 1 from 1 observation 1 2 3 4 5 6 7. A sentence of evasion. It summarizes everything all the properties. Then let's look here. Menas x. 2 is n but ethnics 2 is negative. Although you're right on X you're wrong in your PR function you're going to be harmed big time. Like I often say. The idea. I've never seen the rich forecaster good forecasters. Are sport because they don't get it that the average forecast is what matters. What matters is not to be harmed by these cavities. Now let's take an extreme case. X 3 is I have 9 9 9 zeros and then one of the ration at say a 1000. Okay that's x 3. And. The mean of x3 is 1. Visibly short that one. And yet it was not 1 9 9. Even if that was 300. Okay a lot of zeros and the last observation is 300 K. The mean is going to be points 3 and you still lose money. Okay you're the variable you're forecasting. Game 75. Percent 70 percent below what you are forecasting in the right direction and you still got hammered. So this is to explain the fallacy of forecasting in a very short note. [00:05:46] Thank you for listening to me and have an excellent weekend. Davos Wolrd Economic Forum

CNBC

"People ask 'well what will trigger it (a market correction)?' But it doesn't need a trigger, it's the dynamics of bubbles inherently makes them come to an end eventually," he said. Shiller, who won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2013 for his work on asset prices and inefficient markets, said that markets could "absolutely suddenly turn" and that he believed the bull market was hard to attribute totally to the U.S. political scene. "The strong bull market in the U.S. is often attributed to the situation in the U.S. but it's not unique to the U.S. anyway, so it's hard to know what the world story is that's driving markets up at this time, I think it's more subtle than we recognize," he said. Speaking to CNBC on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos, Switzerland, the Yale University professor said it was hard to define scientifically what could trigger markets to correct. "Something will be invented to explain it once it happens. If you go back to the most famous correction in 1929 there was no (one event) people look back and try to find something but it sounds contrived," he said. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed